The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership or RCEP is a panache of sorts put forward by the ASEAN countries and its six FTA partners. It calls for an EU equivalent amongst the South Asian countries to promote free trade across borders. Though China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and India were expected to join the alliance, India got cold feet and backed off. This article explains the historical baggage India has and the real reason behind the rescind.

Global trade agreements are always a matter of great dismay in developing nations. India had seen several bouts of it right from the times of the British Raj.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, leader of the Indian independence movement, proposed an economic model that he termed 'Grama Swaraj, a self-sustained network of village republics, significantly influencing the first half of free India's existence. Governments were reluctant to come out of this thought shell that limited India's growth in a post-independence period.

But the 1990s saw the country changing its stance towards global trade and commerce. India ended its infamous 'License Raj' for good and started adopting LGP - Liberalisation, Globalisation, Privatisation as its new mantra. The post-Cold War era was ripe with such drastic reforms. Global leaders such as Margaret Thatcher had a significant influence in the changing times. It was a trumpet to the extreme right-wing take over in a sociopolitical sense.

The period witnessed many changes, including the conclusion of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) that paved the way to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) by the mid-'90s. The campuses in India were strife with debates on India's stance on the new trade agreement that would directly benefit an emerging middle class but would act as a death knell for the rural farming economy.

The Conformist media unleashed a FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt) campaign that ensured that the thought leaders split into Aye and Nay! This binary proved costly for the country as the affirmative camp failed to apply due diligence to many of the nuances of the agreement.

Though the farmer's revenue increased for a little while, especially with the cash crops such as latex, it soon took a nosedive crushing the rural economy to a standstill. Food crops such as sugar cane, tea, coffee, cash crops such as cotton and other farm produce were deeply affected in the years to come. It made India a feline that fell in the hot tub.

We should analyse the nations' hesitance to accede to any new open border trade in the above context. India already has a wide trade deficit with China. The increasing presence of China's soft power over the manufacturing sector and its hoarding of metals from iron to lithium is a concern for the neighbour.

Historically, the creation of ASEAN was motivated by a common fear of Communism. But once RCEP becomes functional, China will benefit the most from the agreement. It is detrimental to India's interests.

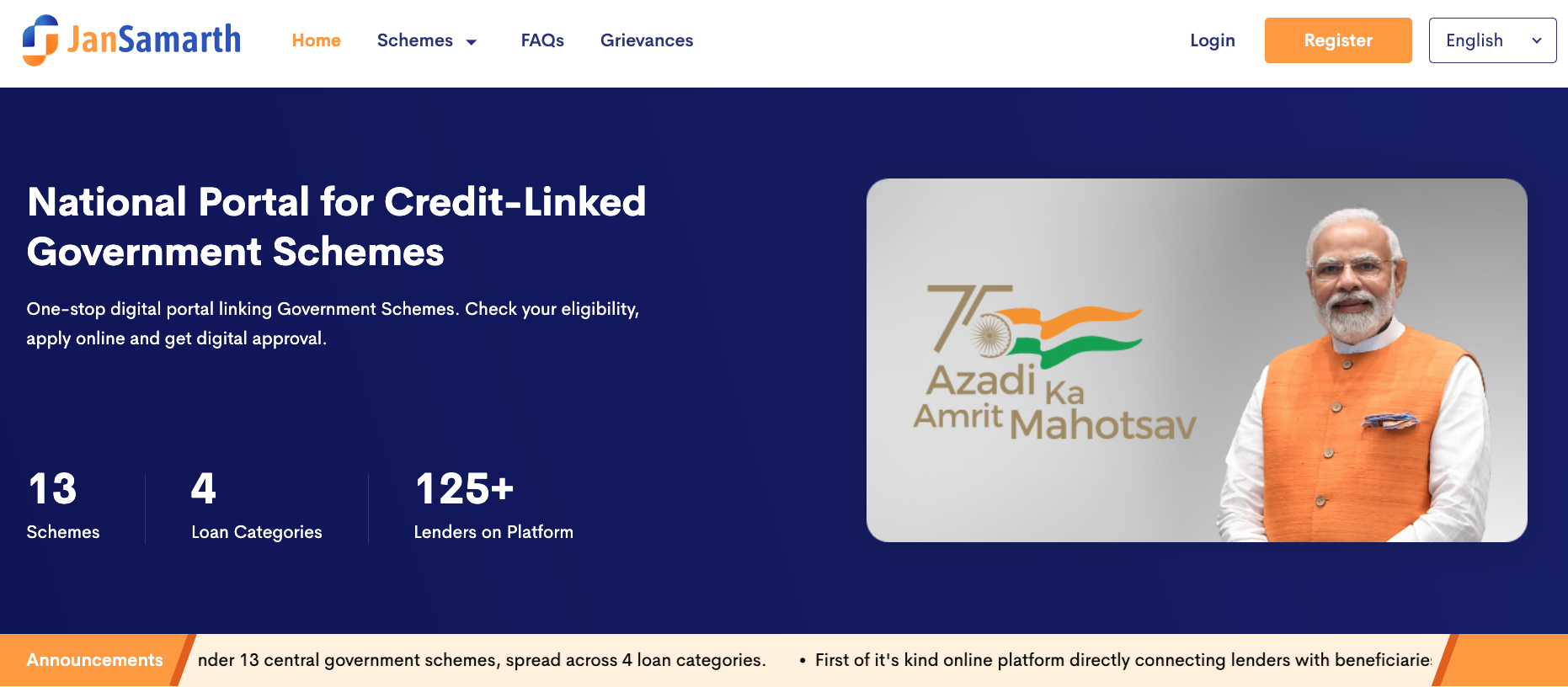

Under the Narendra Damodardas Modi regime, India has gone all out to push the 'make in India' campaign and incentivise various industries to shift their manufacturing plants to India. Ecommerce giants are legally bound to publish the country of origin before selling goods through their online stores. Chinese goods and services companies are discouraged or even blocked from merchandising. The blockade of Alibaba to TikTok sent shock waves across the globe. This increased aggression has everything to do with India's reluctance to align with ASEAN ten and its FTA six.

India cannot forever stay away from the RCEP agreement. The sheer size of the proposed bloc makes it appealing. The 16 nations that constitute the RCEP together account for 45% of the world's population. It drives 39% of the global GDP and 30% of the total trade volume. But still, India is putting up a hedge. The ongoing farmer protests and the need to win every election with a thumping majority groom the central government to put a tight leash over the cross-country trade.

India's main concern was the practice of Chinese companies that churn out cheaper products in China and label them as products from neighbouring countries with which they have an active trade partnership. Thus a toy designed and manufactured in China would come as a Thailandese product or a Laotian product from where they would route it to markets. So India stood for stricter 'rules of origin' wherein such disguised business practices has to be restricted.

India was also apprehensive of a trade war that could cause dumping farm produces at far cheaper rates than India's actual cost of production. So the nation actively stood for safeguard duties to check such moves. Other countries in the alliance were not so willing to cede to India's demands. It forced New Delhi to crouch into a hiding position until things would eventually turn out in its favour. Losing India is costly for the other nations, as we are a global consumer powerhouse by every means.

India has, however, not left the track. Other countries have expressed their willingness to address it's concerns. If this happens to New Delhi's satisfaction, India could still be part of the RCEP.

Comments